An article from “FLIGHT” magazine, January 25, 1934

The Christmas Lunch Served on

Imperial Airways’ Flight for Athens

December 25, 1933

Most people on Christmas Day, whether they be in their own homes, travelling, or in whatever state it has pleased Providence to call them, endeavour to celebrate that anniversary by means of something extra special in the way of food and drink.

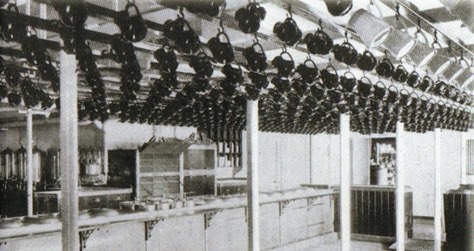

Food being prepared for Imperial Airways and stewards

waiting to pick up whatever is prepared for their next flight.

Imperial Airways always look after their passengers better, perhaps, than any other transport company in the world, and an amusing and effective example of this care is given by the Christmas lunch so carefully arranged for the passengers in Scipio, the fourengined Short flying boat which was to leave Brindisi on the morning of December 25, 1933, for Athens.

The programme did not go quite to schedule owing to delays of the train service which Imperial Airways passengers still unfortunately have to make use of between Pans and Brindisi. The machine actually left Brindisi at 8.15 a.m. on December 26, but the passengers, after consultation, were unanimous in their desire to have the Christmas luncheon which, but for the delay, they would have had on the previous day.

The staff of the Scipio, in command of Capt. F. J. Bailey, had decorated the cabin very carefully with holly, mistletoe and paper streamers, and a Christmas tree had been rigged up. This was suitably decorated and hung with gifts for each of the 14 passengers, in the shape of Imperial Airways diaries with the passengers names stamped thereon. The tree was a fully illuminated one with coloured lamps lit from the ship’s electrical system.

The lunch, which had been supplied by Fortnum & Mason, Ltd., was a great success. The turkey was served cold, but the soup, sausages, potatoes and pudding were all hot. Just how this was done better remain a secret of Imperial Airways, as a cursory glance at the facilities the steward has in his pantry does not appear to offer any solution. The fact remains, however, that when they do give their passengers anything hot it is really hot.

A steward in the pantry on Scipio

The luncheon was served directly after the Scipio had taken off from Corfu, where a landing had been made for fuel. Capt. Bailey, who, as do all Imperial Airways “skippers,” makes a personal matter of the comfort of his passengers, went back into the cabin on several occasions, and after cutting a cake, which had also been provided, presented the diaries from the tree.

![titanics last lunch_thumb[2] titanics last lunch_thumb[2]](https://recipereminiscing.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/titanics-last-lunch_thumb2_thumb.jpg?w=474&h=710)