Food preparation

All types of cooking involved the direct use of fire. Kitchen stoves did not appear until the 18th century, and cooks had to know how to cook directly over an open fire. Ovens were used, but they were expensive to construct and only existed in fairly large households and bakeries. It was common for a community to have shared ownership of an oven to ensure that the bread baking essential to everyone was made communal rather than private. There were also portable ovens designed to be filled with food and then buried in hot coals, and even larger ones on wheels that were used to sell pies in the streets of medieval towns.

But for most people, almost all cooking was done in simple stewpots, since this was the most efficient use of firewood and did not waste precious cooking juices, making potages and stews the most common dishes. Overall, most evidence suggests that medieval dishes had a fairly high fat content, or at least when fat could be afforded. This was considered less of a problem in a time of back-breaking toil, famine, and a greater acceptance—even desirability—of plumpness; only the poor or sick, and devout ascetics, were thin.

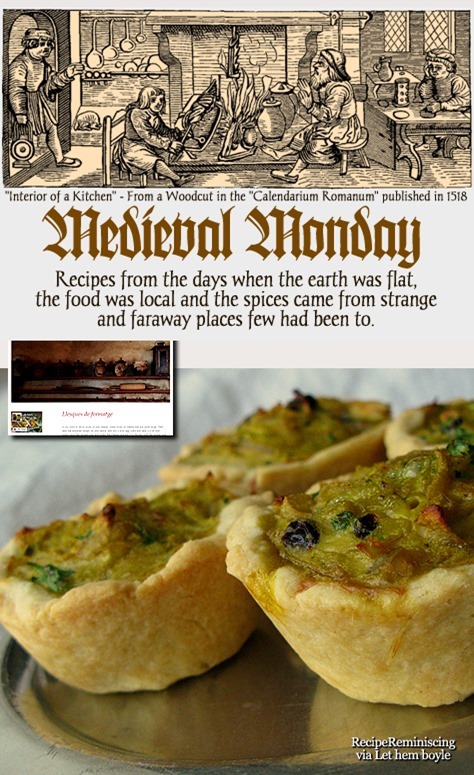

Fruit was readily combined with meat, fish and eggs. The recipe for Tart de brymlent, a fish pie from the recipe collection Forme of Cury, includes a mix of figs, raisins, apples and pears with fish (salmon, codling or haddock) and pitted damson plums under the top crust. It was considered important to make sure that the dish agreed with contemporary standards of medicine and dietetics.

Fruit was readily combined with meat, fish and eggs. The recipe for Tart de brymlent, a fish pie from the recipe collection Forme of Cury, includes a mix of figs, raisins, apples and pears with fish (salmon, codling or haddock) and pitted damson plums under the top crust. It was considered important to make sure that the dish agreed with contemporary standards of medicine and dietetics.

This meant that food had to be “tempered” according to its nature by an appropriate combination of preparation and mixing certain ingredients, condiments and spices; fish was seen as being cold and moist, and best cooked in a way that heated and dried it, such as frying or oven baking, and seasoned with hot and dry spices; beef was dry and hot and should therefore be boiled; pork was hot and moist and should therefore always be roasted. In some recipe collections, alternative ingredients were assigned with more consideration to the humoral nature than what a modern cook would consider to be similarity in taste. In a recipe for quince pie, cabbage is said to work equally well, and in another turnips could be replaced by pears.

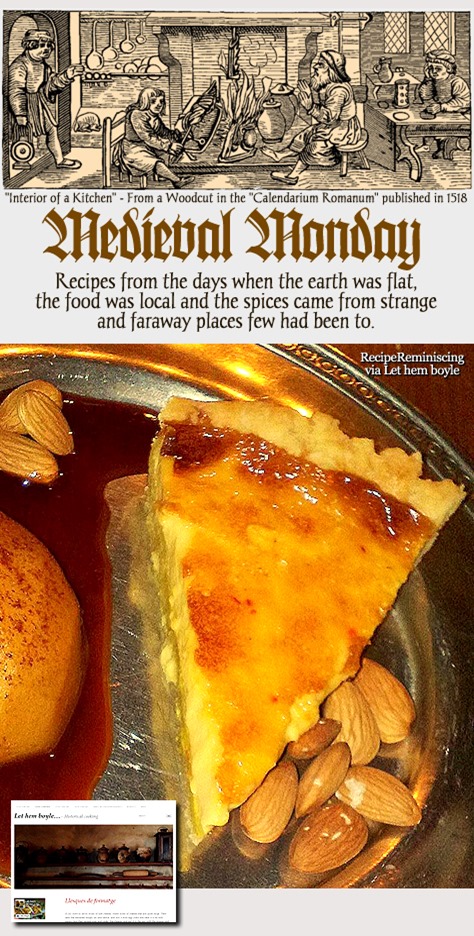

The completely edible shortcrust pie did not appear in recipes until the 15th century. Before that the pastry was primarily used as a cooking container in a technique known as ‘huff paste’ . Extant recipe collections show that gastronomy in the Late Middle Ages developed significantly. New techniques, like the shortcrust pie and the clarification of jelly with egg whites began to appear in recipes in the late 14th century and recipes began to include detailed instructions instead of being mere memory aids to an already skilled cook.

Medieval kitchens

In most households, cooking was done on an open hearth in the middle of the main living area, to make efficient use of the heat. This was the most common arrangement, even in wealthy households, for most of the Middle Ages, where the kitchen was combined with the dining hall. Towards the Late Middle Ages a separate kitchen area began to evolve. The first step was to move the fireplaces towards the walls of the main hall, and later to build a separate building or wing that contained a dedicated kitchen area, often separated from the main building by a covered arcade. This way, the smoke, odors and bustle of the kitchen could be kept out of sight of guests, and the fire risk lessened. Few medieval kitchens survive as they were “notoriously ephemeral structures”.

Many basic variations of cooking utensils available today, such as frying pans, pots, kettles, and waffle irons, already existed, although they were often too expensive for poorer households. Other tools more specific to cooking over an open fire were spits of various sizes, and material for skewering anything from delicate quails to whole oxen. There were also cranes with adjustable hooks so that pots and cauldrons could easily be swung away from the fire to keep them from burning or boiling over. Utensils were often held directly over the fire or placed into embers on tripods. To assist the cook there were also assorted knives, stirring spoons, ladles and graters.

Many basic variations of cooking utensils available today, such as frying pans, pots, kettles, and waffle irons, already existed, although they were often too expensive for poorer households. Other tools more specific to cooking over an open fire were spits of various sizes, and material for skewering anything from delicate quails to whole oxen. There were also cranes with adjustable hooks so that pots and cauldrons could easily be swung away from the fire to keep them from burning or boiling over. Utensils were often held directly over the fire or placed into embers on tripods. To assist the cook there were also assorted knives, stirring spoons, ladles and graters.

In wealthy households one of the most common tools was the mortar and sieve cloth, since many medieval recipes called for food to be finely chopped, mashed, strained and seasoned either before or after cooking. This was based on a belief among physicians that the finer the consistency of food, the more effectively the body would absorb the nourishment. It also gave skilled cooks the opportunity to elaborately shape the results. Fine-textured food was also associated with wealth; for example, finely milled flour was expensive, while the bread of  commoners was typically brown and coarse. A typical procedure was farcing (from the Latin farcio, “to cram”), to skin and dress an animal, grind up the meat and mix it with spices and other ingredients and then return it into its own skin, or mold it into the shape of a completely different animal.

commoners was typically brown and coarse. A typical procedure was farcing (from the Latin farcio, “to cram”), to skin and dress an animal, grind up the meat and mix it with spices and other ingredients and then return it into its own skin, or mold it into the shape of a completely different animal.

The kitchen staff of huge noble or royal courts occasionally numbered in the hundreds: pantlers, bakers, waferers, sauciers, larderers, butchers, carvers, page boys, milkmaids, butlers and numerous scullions. While an average peasant household often made do with firewood collected from the surrounding woodlands, the major kitchens of households had to cope with the logistics of daily providing at least two meals for several hundred people. Guidelines on how to prepare for a two-day banquet can be found in the cookbook Du fait de cuisine (“On cookery”) written in 1420 in part to compete with the court of Burgundy by Maistre Chiquart, master chef of Amadeus VIII, Duke of Savoy. Chiquart recommends that the chief cook should have at hand at least 1,000 cartloads of “good, dry firewood” and a large barnful of coal.

Professional cooking

The majority of the European population before industrialization lived in rural communities or isolated farms and households. The norm was self-sufficiency with only a small percentage of production being exported or sold in markets. Large towns were exceptions and required their surrounding hinterlands to support them with food and fuel. The dense urban population could support a wide variety of food establishments that catered to various social groups. Many of the poor city dwellers had to live in cramped conditions without access to a kitchen or even a hearth, and many did not own the equipment for basic cooking. Food from vendors was in such cases the only option.

Cookshops could either sell ready-made hot food, an early form of fast food, or offer cooking services while the customers supplied some or all of the ingredients. Travellers, such as pilgrims en route to a holy site, made use of professional cooks to avoid having to carry their provisions with them. For the more affluent, there were many types of specialist that could supply various foods and condiments: cheesemongers, pie bakers, saucers, waferers, etc. Well-off citizens who had the means to cook at home could on special occasions hire professionals when their own kitchen or staff could not handle the burden of throwing a major banquet.

Cookshops could either sell ready-made hot food, an early form of fast food, or offer cooking services while the customers supplied some or all of the ingredients. Travellers, such as pilgrims en route to a holy site, made use of professional cooks to avoid having to carry their provisions with them. For the more affluent, there were many types of specialist that could supply various foods and condiments: cheesemongers, pie bakers, saucers, waferers, etc. Well-off citizens who had the means to cook at home could on special occasions hire professionals when their own kitchen or staff could not handle the burden of throwing a major banquet.

Urban cookshops that catered to workers or the destitute were regarded as unsavory and disreputable places by the well-to-do and professional cooks tended to have a bad reputation. Geoffrey Chaucer’s Hodge of Ware, the London cook from the Canterbury Tales, is described as a sleazy purveyor of unpalatable food. French cardinal Jacques de Vitry’s sermons from the early 13th century describe sellers of cooked meat as an outright health hazard.

While the necessity of the cook’s services was occasionally recognized and appreciated, they were often disparaged since they catered to the baser of bodily human needs rather than spiritual betterment. The stereotypical cook in art and literature was male, hot-tempered, prone to drunkenness, and often depicted guarding his stewpot from being pilfered by both humans and animals. In the early 15th century, the English monk John Lydgate articulated the beliefs of many of his contemporaries by proclaiming that “Hoot ffir [fire] and smoke makith many an angry cook.

Text from Wikipedia